On any given day at my day job, although the purpose or audience of the maps I make and the techniques I use are quite varied, I’m held to standards (and deadlines) that prevent me from branching out, cartographically speaking. Thus, the point of this website: to share some of the more creative aspects of my personal cartographic interests.

One of my most ambitious personal projects (the Alaska Literary Map) was unveiled at the Alaska Surveying and Mapping Conference in 2016 and the map won a contest – with a prize!

I was so excited, only to discover that the prize was…

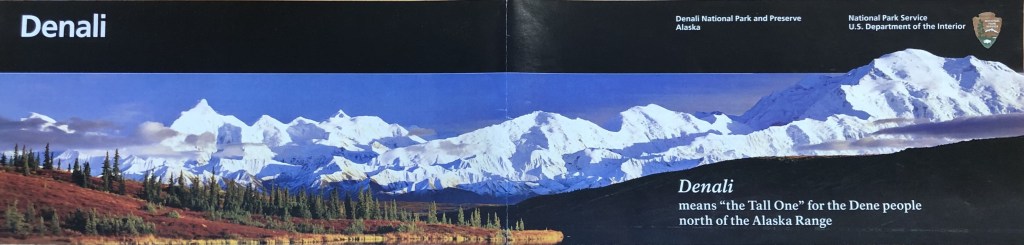

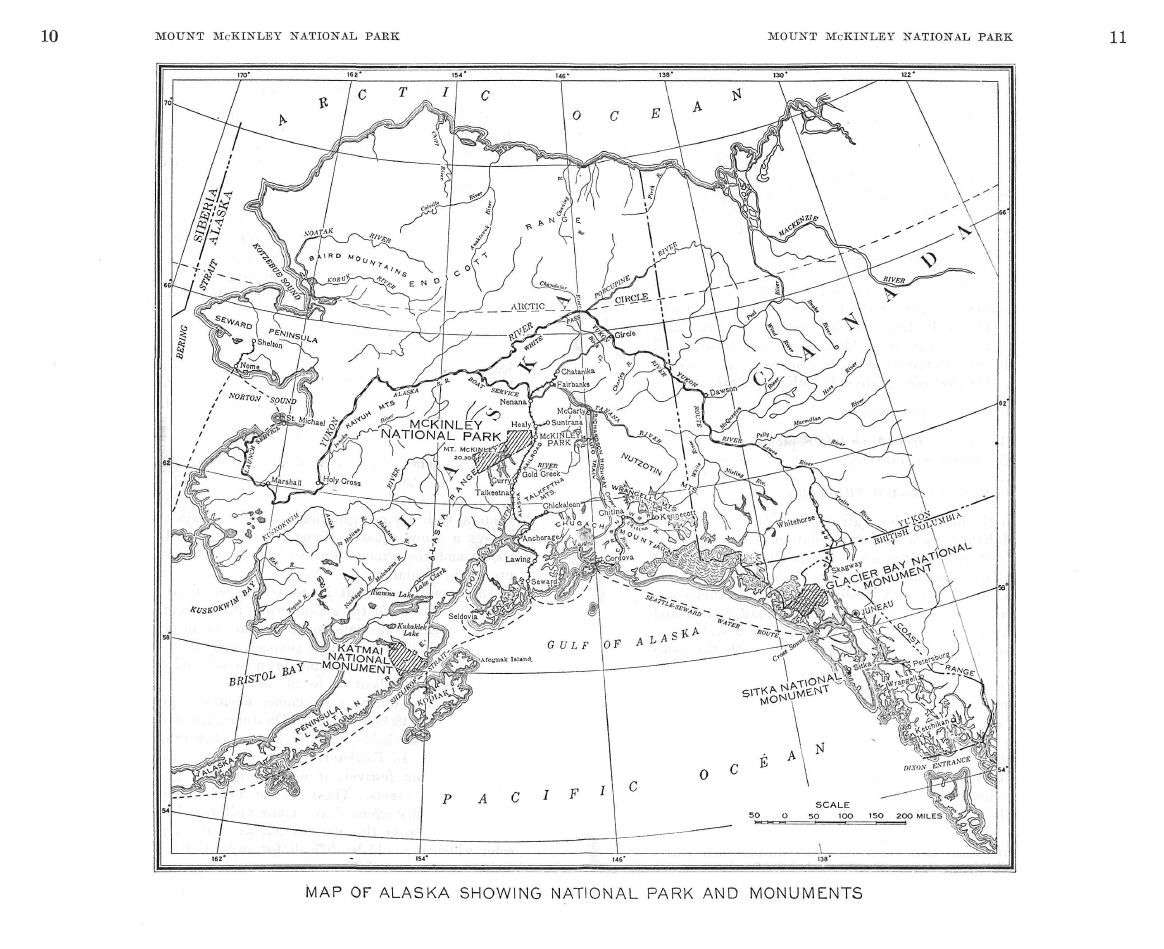

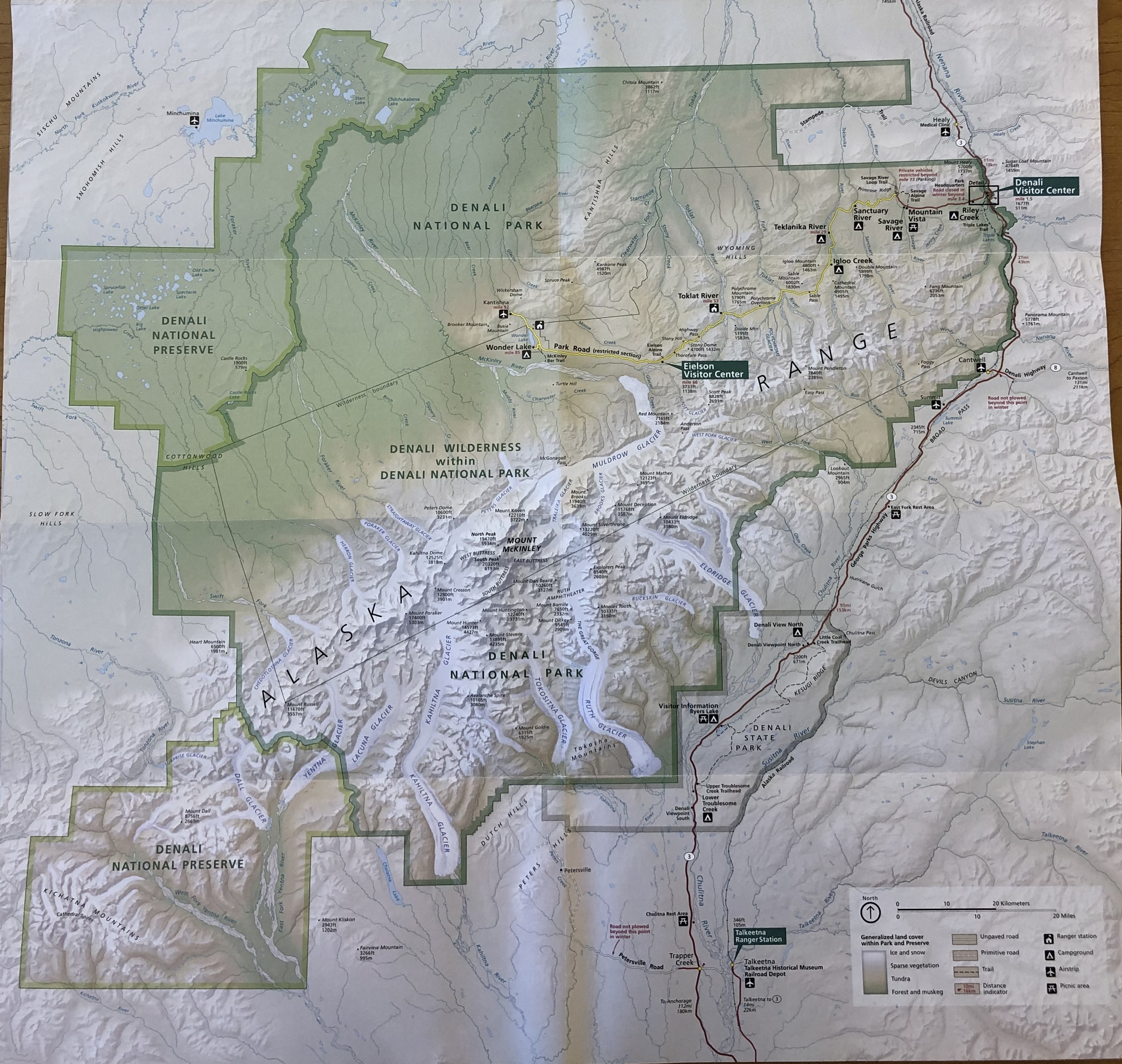

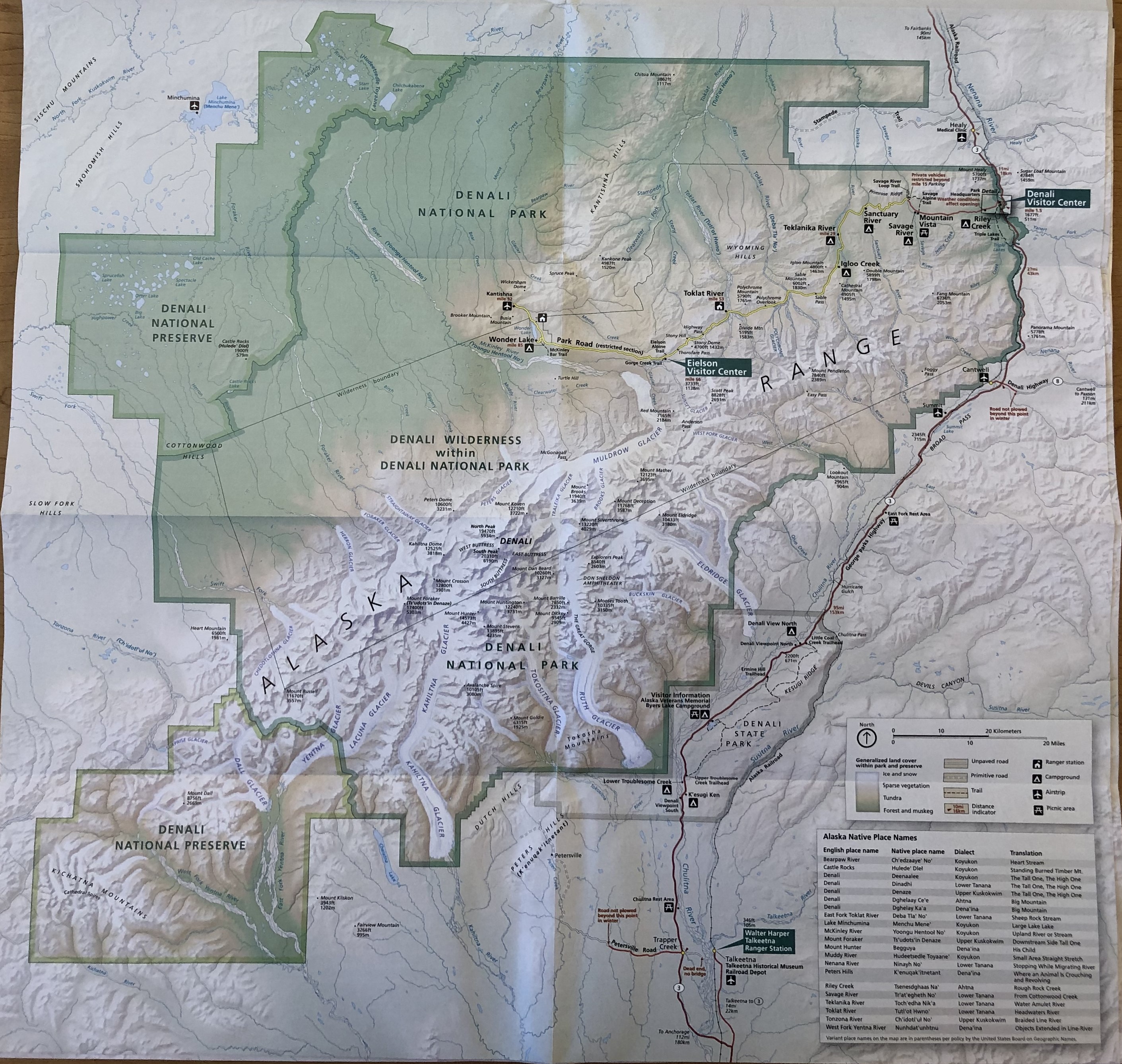

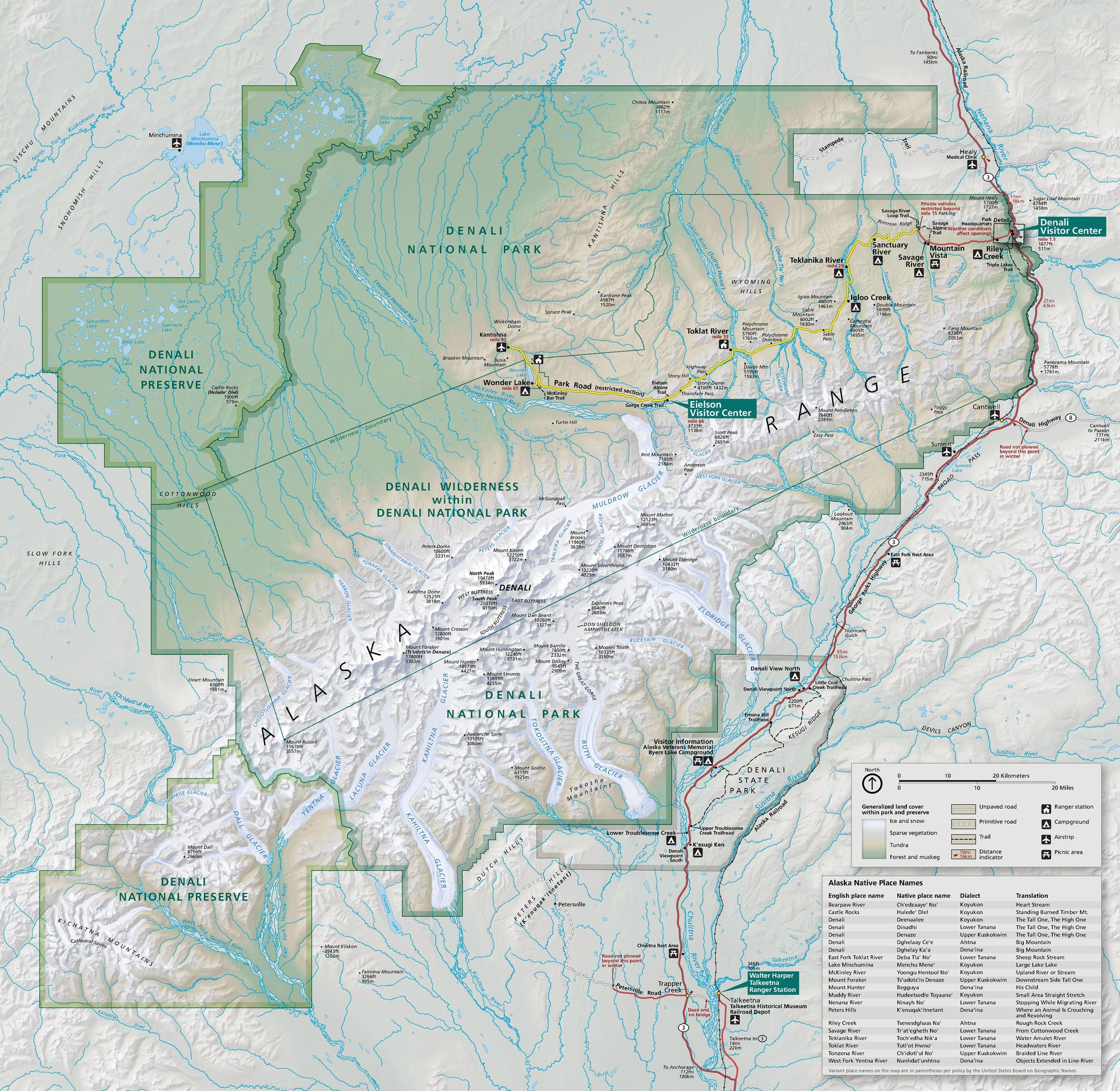

….a map of Denali National Park and Preserve.

Now, the prize map wasn’t a map that I myself originally created, but it was one that I am tasked with updating regularly, as it was a version of the map used in the NPS park brochure.

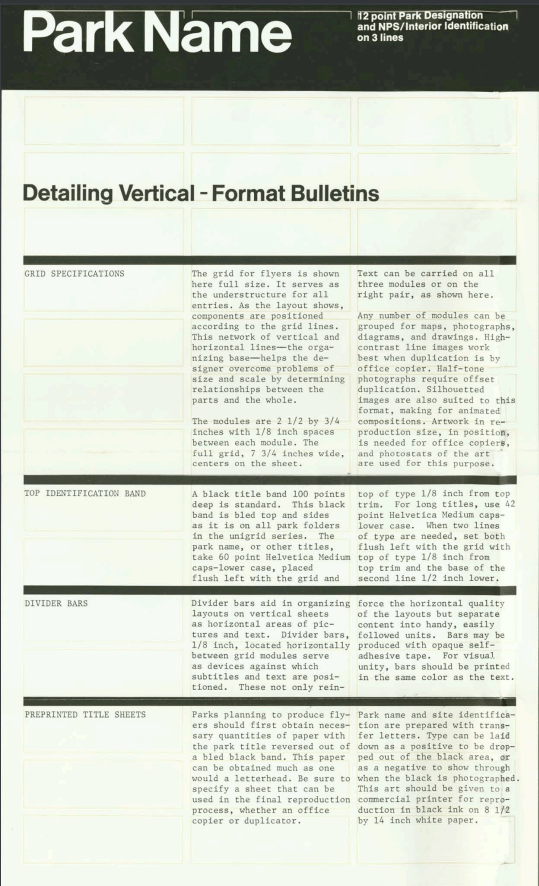

Even if you have never visited a National Park, the brochure may be recognizable with the iconic black bands, sans serif font, and a National Park Service arrowhead logo. The NPS has been using this style of branding for as long as the majority of American adults can remember.

The maps in these Park Service brochures are so popular that the brochures themselves are often synonymous with “park maps”. Text and graphics may come and go over the years, but very few unit brochures in the National Park System omit a map. These brochures are often referred to internally as the Unigrid; to maintain the aesthetic consistency of the map, these publications are produced by the Harpers Ferry Center (HFC) Cartography team with data provided from a park or region.

These Unigrid brochures are not only popular, but also prolific. Most visitors to a park receive one when paying an entrance fee or pick one up when at a visitor center. With Denali’s annual visitation rate surpassing half a million people in recent years, our park purchases brochures by the tens of thousand. Imagine how many brochures Grand Canyon or Yosemite uses annually! Although people might keep these brochures as a memento from their trip, in any given year, an individual brochure is only worth about as much as the paper it is printed on.

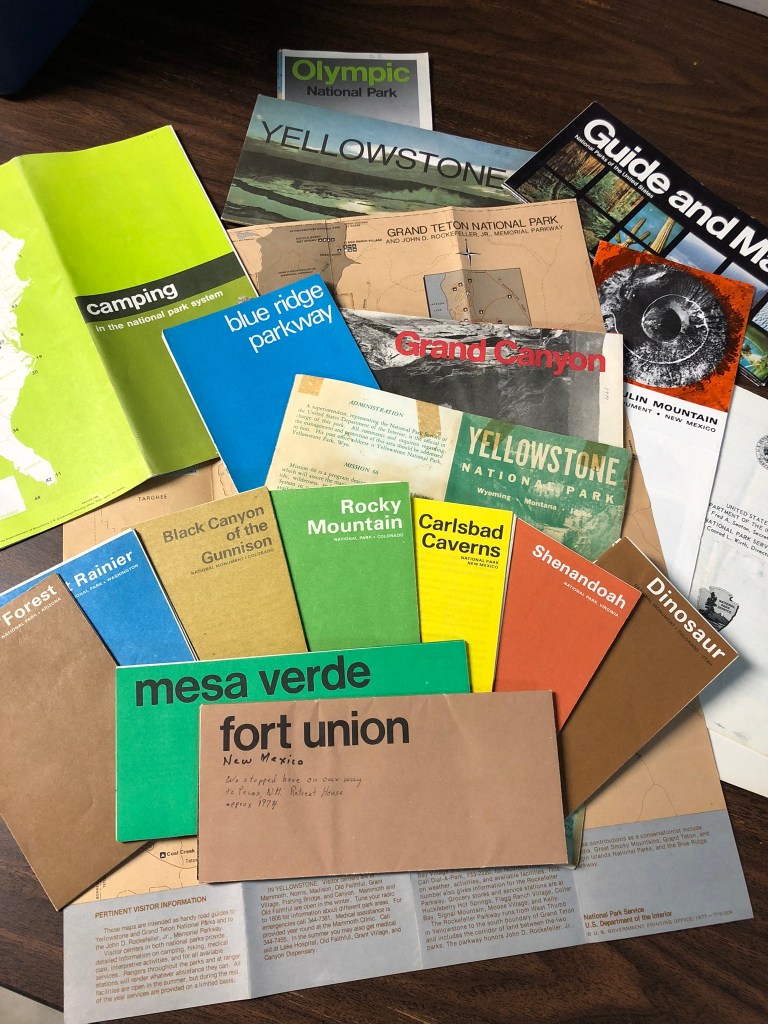

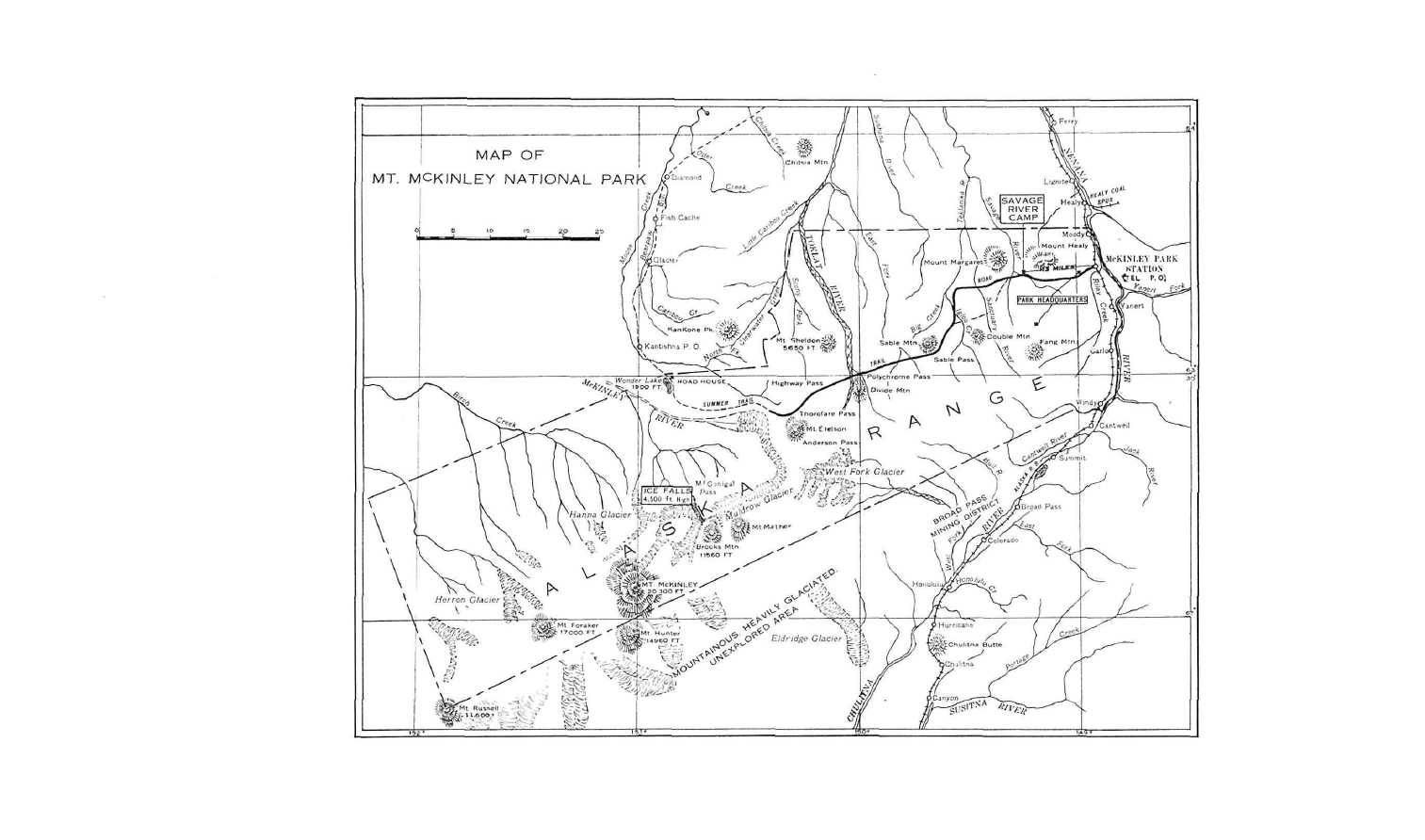

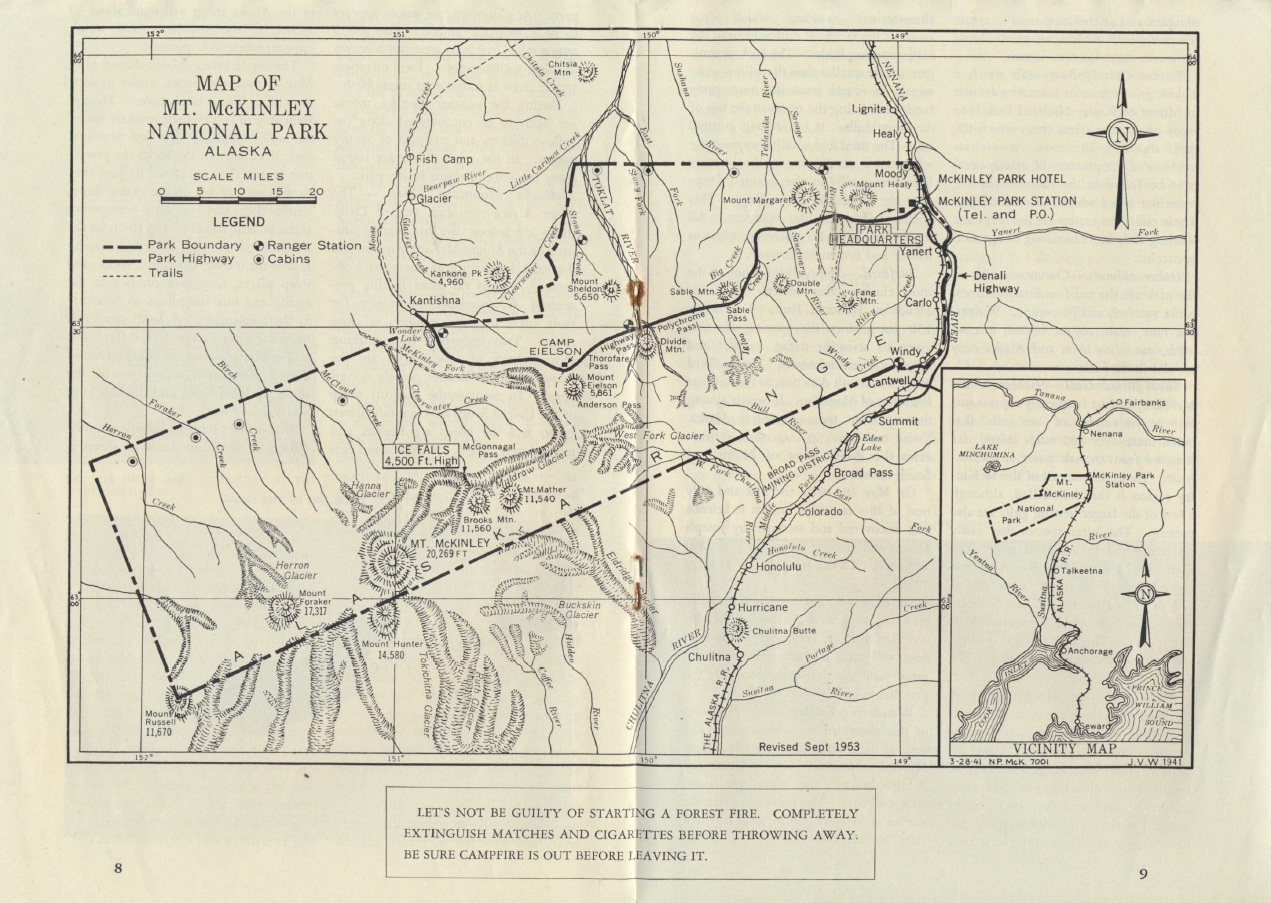

But as any collector knows, it is often the mundane items that are used up or tossed first, which become the most valuable. Which is why maps that were created before the Unigrid standardized NPS branding across the nation in 1977 (called pre-Unigrid maps) are often the hardest to come by and are the most “valuable”.

This winter, when cleaning out my father’s map collection back in Colorado, I discovered a set of pre-Unigrid park unit maps from across the nation, dating mostly to the late 60’s and early 70’s. Later that week, my aunt and uncle also gave me a vast collection of their National Park maps from the 1950’s. It is safe to say that out of all of the material items I inherited from my family, this map collection is my most valued possession, not only because I am both a carto-nerd and a NPS cartographer, but because of the increasing rarity of pre-Unigrid maps. To understand my excitement, it helps to understand the history of the NPS cartography.

History of the Unigrid

The National Park Service is perhaps the most self-aware of agencies in terms of historic documentation and has a collection of information on the background of the Unigrid; I highly recommend the two links below to learn more.

What is the National Park Service Unigrid?

The Story of Unigrid Brochures: What’s in Your Collection?

Cartography of the Unigrid

Now, that we know a little about the concepts and changes around the Unigrid as a whole, let’s focus a bit more on the details of the maps.

As I mentioned before, the Harpers Ferry Center (HFC) is tasked with updating the brochures and maps when necessary. Nancy Haack, who studied under Arthur Robinson (astute readers of map marginalia will recognize that name as the projection used by National Geographic until the 90’s), was hired by the HFC as the first NPS professional cartographer, working there from 1977 to 2011. Odds are, if you’re looking at a recent brochure map, she had a hand in designing or standardizing labels, features, scale, colors, etc. However, I’ll tell you what I think is one of her most impressive accomplishments further down in this blog.

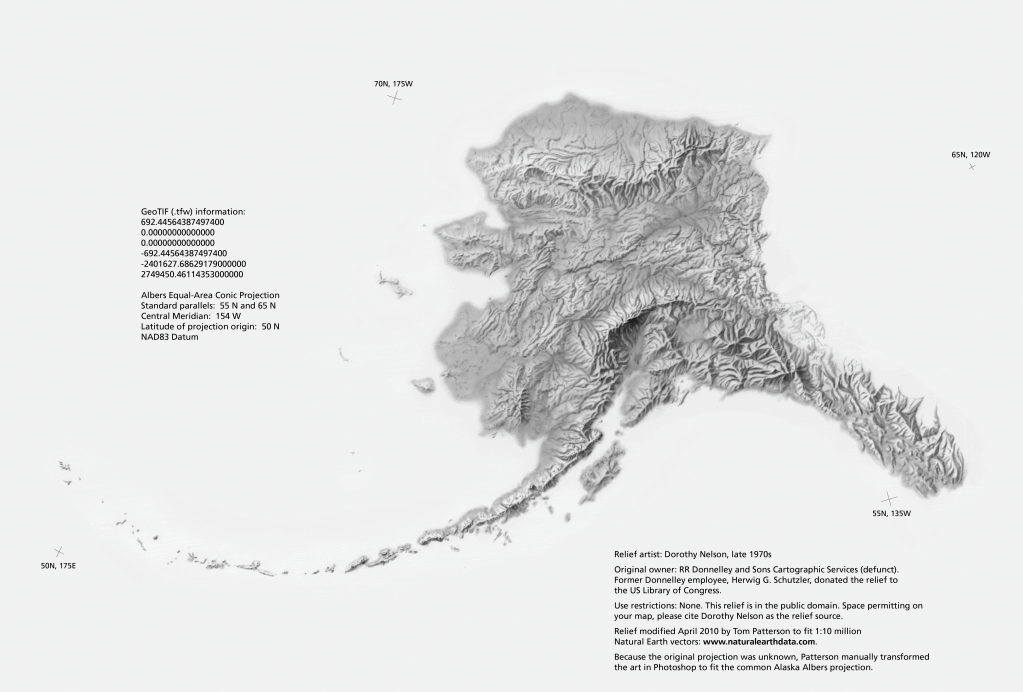

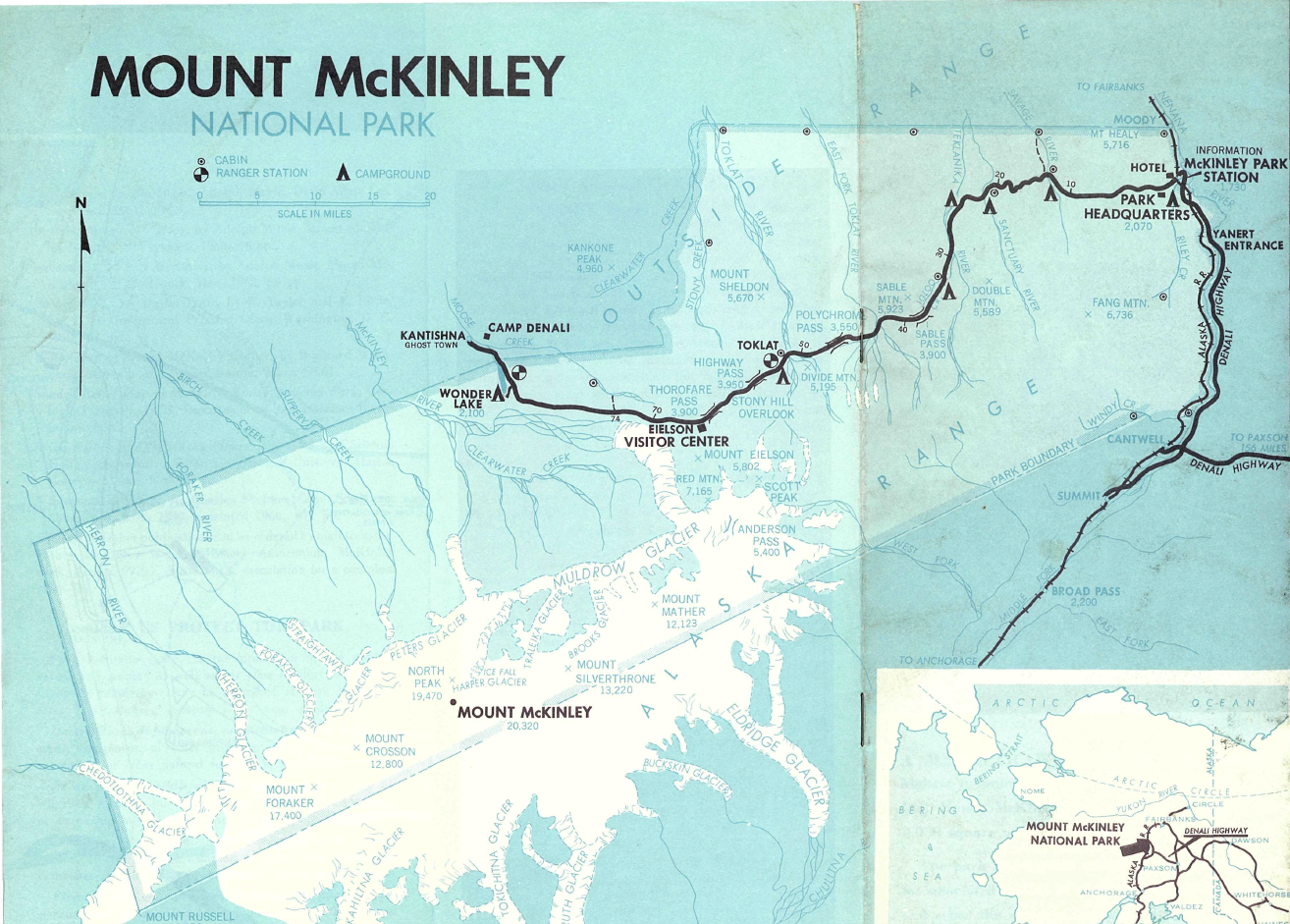

Prior to the HFC, most park maps were “in the dark ages of line-work cartography”, with simple lines depicting elevation, park boundaries, roads, etc. When the HFC was created in 1970, the center’s director had a new vision for standardizing park maps. This included adding shaded relief to simplify terrain, as made popular through cartographic shops such as swisstopo and National Geographic (I highly suggest the ReliefShading website for a deeper dive into the art, science, history, and characters of shaded relief).

Shortly after the HFC was created, RR Donnelley Cartographic Services was contracted to make shaded relief for the NPS for the first formative years. However, Bill von Allmen is often credited as the first (or one of the first) NPS employed cartographer who did shaded relief in-house. Coming to the NPS from the USGS in the 1960’s, he received training in 1974 from swisstopo on relief shading, and made over 80 shaded relief layers for park units before he retired from the NPS in 1990, though he continued to do contract work into the 90’s.

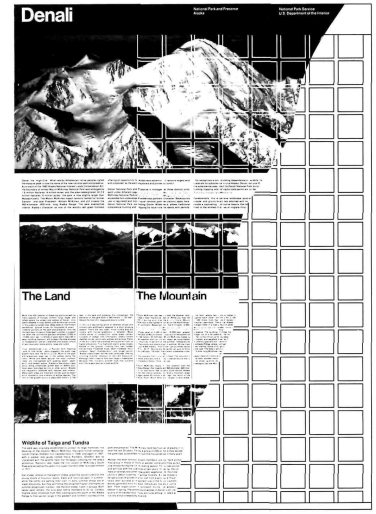

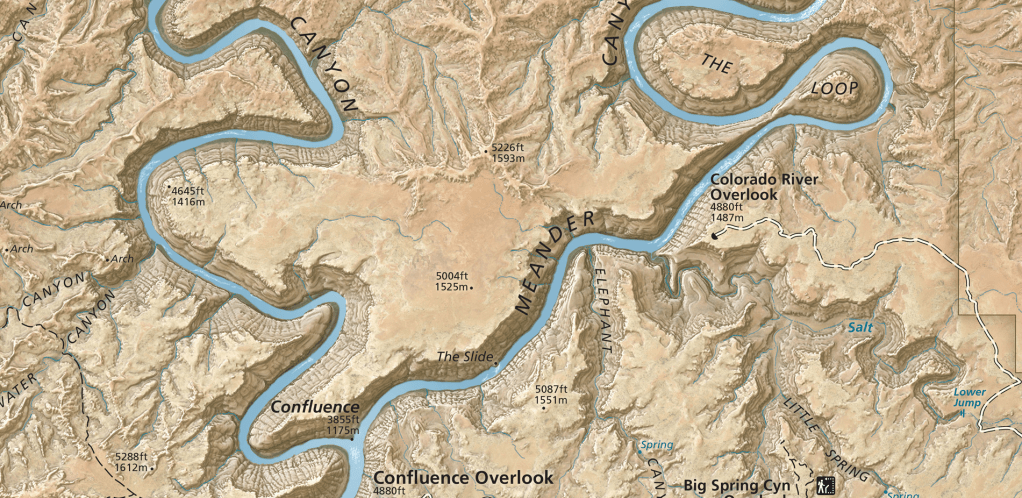

The HFC team also included perhaps one of the most skilled U.S. cartographers, Tom Patterson, whose continued improvements on the Unigrid maps between 1992 and 2018 contributed to making these maps a beloved collectors item by the public. Patterson came to HFC at a time when hand-drawn shaded relief maps were being replaced by digitally generated products. Although Patterson did some hand-drawn shading early in his career, by the time he retired, all the park unit maps that had previously used manual relief shading were converted to digital shading.

Patterson’s knowledge of the cartographic principles of shaded relief combined with his skill at computer-aided design put him in the foreground of NPS realism. In addition to shaded relief, realism uses hypsometric tinting, texture shading, illumination, and other cartographic tricks to reduce the use of lines in favor of a more organic, natural appearance. Examples below are drawn from his Shaded Relief website.

Since Patterson’s retirement, among other accomplishments, he has also made his name in advancing cartography through co-authoring a new projection and assisting other in making many hand-drawn shaded relief datasets available to the public. John Nelson recently took advantage of the large collection of publicly available manual shaded relief to create digital products using historic relief.

The combined efforts of the HFC cartographic branch created an incredibly strong branding of NPS maps that continues to live on today as some of the most recognizable and aesthetically pleasing maps produced by the federal government, perhaps second only to the topographic maps produced by the U.S. Geologic Survey in the second half of the 20th century.

Change as a Constant

Once, when I told someone that I was a cartographer for the National Park Service, they brusquely asked, “Don’t we already have a map of the park?”, questioning the necessity of my job. However, a keen reader of any Unigrid map will notice small, but consistent, changes to the maps over the years, which eventually add up to create vastly different maps after the passage of the years.

In my twelve years at Denali, we have updated the brochure and map at least six times. Here are just a few of the cheats I use to determine the date of any brochure I pick up (most of the brochures are stamped with a year the brochure was printed, but not every printing requires a map change and the maps are stand alone products that can be published without the brochure):

- 1917-1920’s – Creation of the park and infrastructure

- 1930’s through 1940’s – Construction of patrol cabins and completion of the park road

- 1953 – Short lived adoption of 20,269 ft for the height of the mountain

- 1956 – Adoption of Bradford Washburn’s height of Denali at 20,320 ft

- mid to late 1970’s – The federal government’s failed attempt to convert to the metric system and the addition of hillshading

- 1980 – The passage of ANILCA, resulting in the “new park” and “preserve” additions

- 2011 – Addition of hypsometric tinting and change from hand-drawn to digital hillshading

- 2016 – Brochure and Map: Reinstatement of the name “Denali” to the tallest peak in North America and new peak height, renamed Talkeetna Ranger Station to Walter Harper Visitor Center

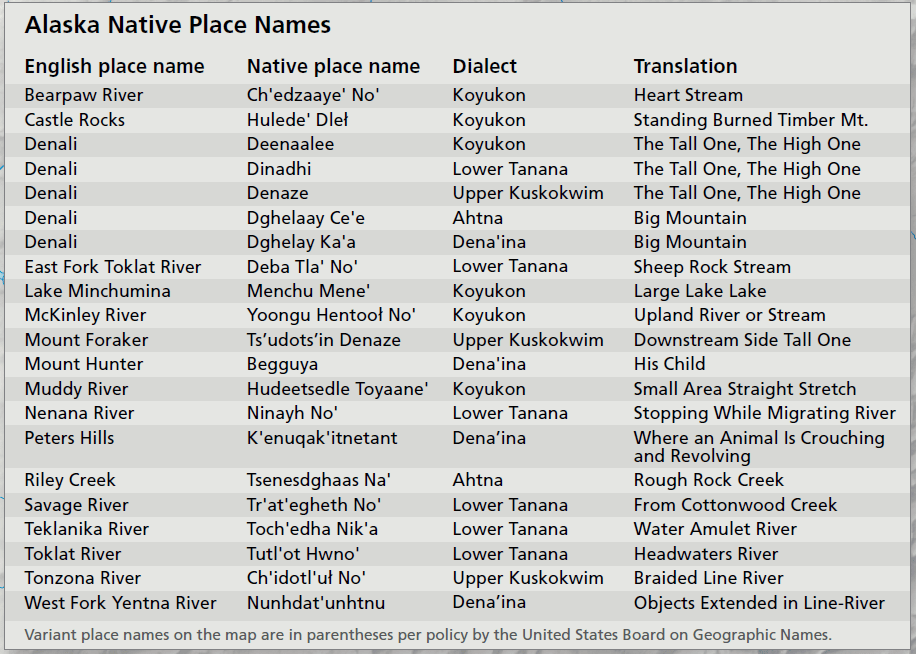

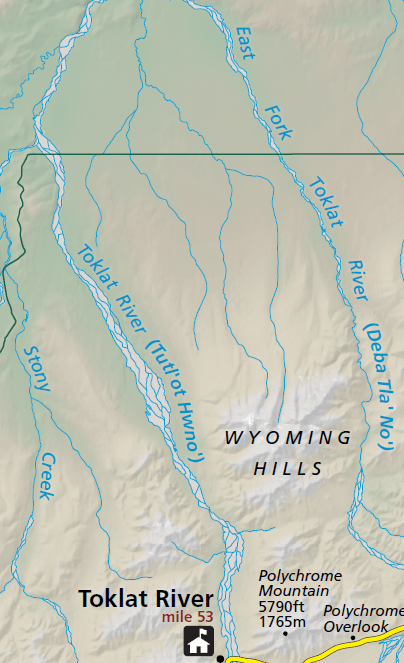

- 2018 – Addition of 17 Native Place Names

- 2025 – Keep reading!

A New Era for Very Old Names

One of my favorite things about geographic place names in Alaska is how many Native place names have been retained (or used as English cognates) compared to other areas in the Americas that were colonized at an earlier period in time.

Recently, I watched a presentation by Dr. Gerad Smith on the methods behind the creation of an Alaska Native Place Names Atlas (Smith, Gerad, and James Kari. 2023. The Web Atlas of Alaska Dene Traditional Place Names. ArcGIS Storymap, published online November 15, 2023). He mentioned two interesting facts during this presentation.

First, of all the English names in the federally maintained Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) and all the currently documented Dene names in Alaska, there is only about a 10% overlap between the features named by both languages. In other words, colonizers from places like Russia, Britain, Spain, France, and the U.S., often assigned names to different topographic features than Dene people. For example, both languages would name a major river, but the English language might name prominent peaks around the river while the Dene language might name larger scale features of the river useful for navigation.

Second, of the features that both English and Native cultures determined worthy of naming, about 30% of those features have retained some semblance of the Native origin in the current English form, either as an anglicized version (e.g., the English name of “Denali” which was derived from the Koyukon name) or the translation of the Native name (e.g., a feature named after an animal, like “Sheep Creek”).

As tribes, communities, and researchers continue to work towards increasing our knowledge about Native place names, there is much more information to be gleaned from this dataset, which I will explore in another blog post.

Over the years, National Park units have incorporated more Indigenous place names onto park maps, even in areas where the Native names may not be part of the Federal Board of Geographic Names Information System. Part of this cartographic change started with the HFC cartographer Nancy Haack when she began work on the Hawai’i park maps in the 1990’s. At that time, as a federal cartographer, she was limited to the standards set by the US Board of Geographic Names. However, park units in Hawai’i requested updated maps with Native Hawaiian names and spellings. Haack worked with the Board, the USGS, the state of Hawai’i, and the park units in Hawai’i to gain recognition of the Native names, resulting in the first uses of these names on NPS maps. This was the start of a shift in cartography that I feel is Haack’s greatest gift to the NPS.

Since the 90’s, the NPS has continued to make gains in sharing more about the unique cultures that live in and around the parks. Another example that continues to make some gains in the technological world is a Native place name map with embedded audio, such as that of the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore in Wisconsin, that is hosted on a park website. And someday, I dream of an offline mobile map app that allows users to listen to the pronunciation of place names of the landscapes they are viewing in real time, along with Indigenous stories and history, for any park unit they are visiting in the nation.

As for us here in Denali, we requested about 17 Alaska Native Place Names to be added to our park map in 2018. This request was met mostly through an inset box, with English names, Native names, and translations, though some features had enough cartographic real estate on the map to include the Native place name in parentheses.

However, even with these changes, many of the Native place names on maps are treated as a secondary name, written in parentheses or italicized, giving the impression of honoring Indigenous cultures only as a kind of afterthought. As the trend continues to incorporate recognition of the cultures who first stewarded the lands we now call National Parks, what I find the most exciting is the official designation of new sites using only Native place names.

Just this summer, Denali opened a wayside at Milepost 231 along the Parks Highway. This new trailhead parking for the Oxbow and Triple Lake trails is officially named Tsenesdghaas Na’.

Although there is an English translation provided (meaning “rough rock creek”), there is no English name associated with this site, and I love that. I am looking forward to submitting this place name to the HFC for updating our Unigrid map and I’m looking forward to a few other projects that are planned for the official opening of the trailhead in 2025.

Given the rich cartographic history of the NPS, this puts into perspective what was so exciting about inheriting on old map stash, both from my personal interests, but also within the world of my profession and my employer.

Last month marked my 10th year in my current position as a cartographer with the NPS, and I am still in awe of the national treasures and history that myself and my colleagues throughout the nation are tasked with preserving for future generations. It is both humbling and exciting to play even a small part in the history of the National Parks, mapping this corner of our public lands

Checking out the Tsenesdghaas Na’ trailhead last week.

You must be logged in to post a comment.