We have reached the winter solstice, a special day in the northern latitudes. In places that receive sun, it is the darkest day of the year. For places so far north as to be in the polar night, it is the mid-point of the darkness. Either way, after December 21, the earth begins to tilt back towards the sun and daylight eventually returns.

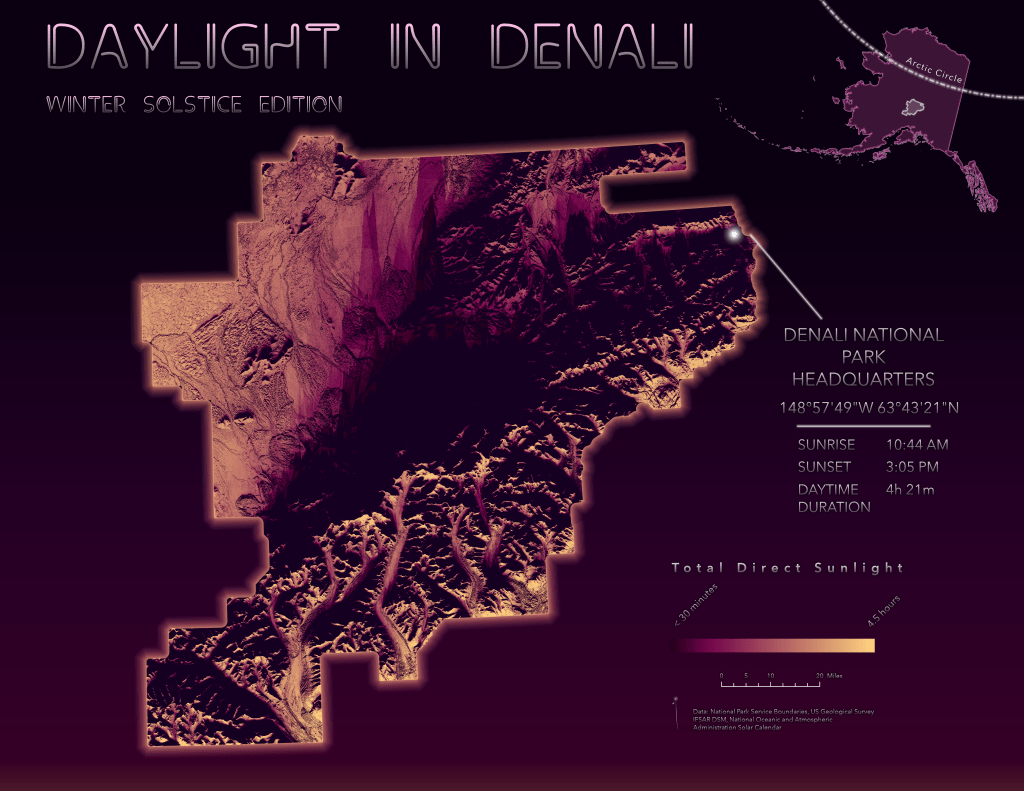

In places north of the Arctic Circle (66° 34′ N), the sun never rises on the winter solstice, while in place south of the Arctic Circle, like Denali (63° 43′ N), the sun will rise but only for a few hours. The daylight duration in Denali during the winter solstice is usually around 4.5 hours, with the sun at it’s highest point on the horizon at solar noon (1 pm due to daylight savings time).

However, one thing that is often overlooked in the discussion of how the surrounding topography also affects the amount of direct sunlight (otherwise called direct radiation) an area will receive. Because the Alaska Range runs straight through the heart of Denali National Park and Preserve, the vast relief often blocks the sun from reaching valley floors. Where I work, the sun will not peak above the hills to the south from roughly November 17 to January 17. Although I can head south or north to feel the sun on my face, even my cabin in Healy is devoid of direct sunlight for many weeks at a time.

In 2020, I created a map for work that showed the areas of the park that receive direct sunlight and how much sunlight each area receives. One of my favorite things about this map is the ability to see the shadow of The Mountain stretching many miles to the north. Mushers who travel through this shadow have taken some phenomenal photos – I highly encourage readers to look at those of Miki and Julie Collins, two residents of Lake Minchumina.

Because it was about 40 below outside, today seemed like a good a day to recreate the map and make some additions/clarifications to it.

Using the IFSAR DSM clipped to the Denali park boundaries, I created a slope and aspect raster using the Surface Parameters tool. This was key to having a smooth looking output from the next step, the Raster Solar Radiation tool. In 2020, I used the soon-to-be deprecated Area Solar Radiation tool. One tradeoff between these tools is that the older Area Solar Radiation tool allowed user-defined “look angles”, while the newer Raster Solar Radiation tool outputs to a multi-dimensional raster (Esri Cloud Raster Format, .CRF). Given that I’m not modeling tall, narrow features like wind turbines and that I prefer to work with multi-dimensional data, I used the Raster Solar Radiation tool based on hourly calculations.

The output showing direct sunlight is from the Direct Duration Raster which displays based on the unit of insolation parameter (I used hourly this time, but in 2020 used 30 minutes intervals). I used the summary statistics tool to create a sum of all time slices for the duration variable.

The other output is Solar Radiation as show in kWh/square meter. Even on The Mountain, the highest point in the Alaska Range and therefore, the area that would in be the first and last spot to receive daylight, the total solar radiation for the entire day is 0.3 kWh per square meter, which is very low.

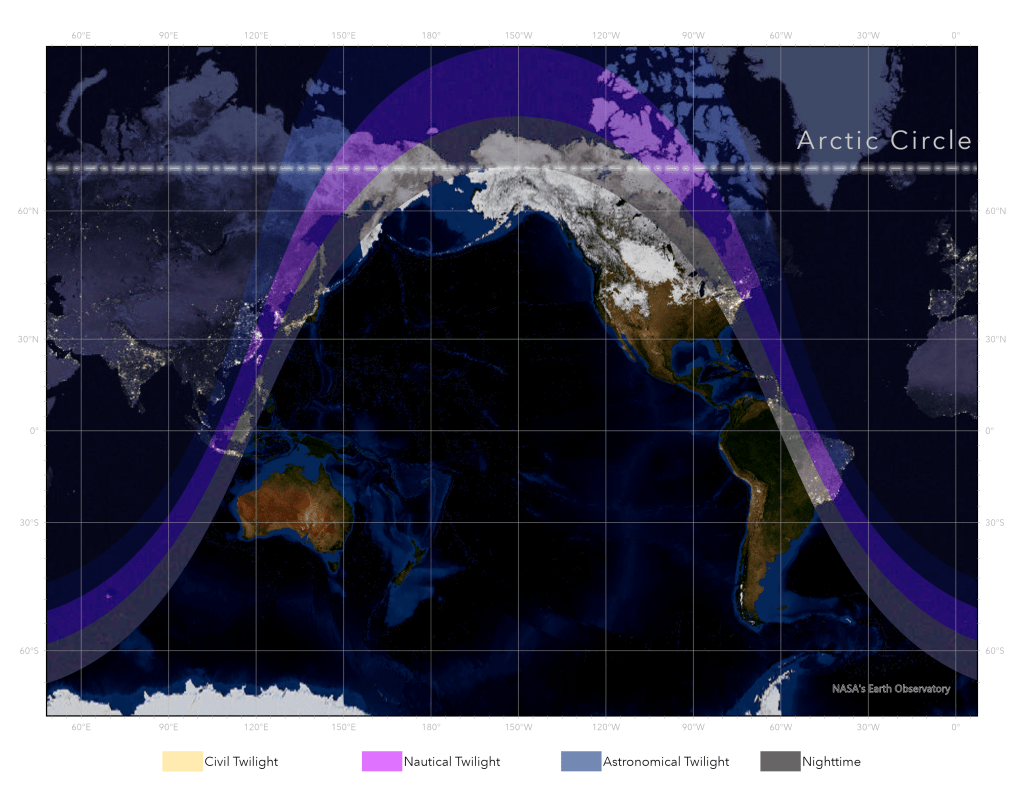

Another way to visualize the daylight is through a daylight terminator map. Here is a daylight terminator map in real-time created by Esri, while below is one I created for winter solstice in Denali. I attempted using a global scene with 3D points for poles to depict the area of daylight termination, but would probably be better served attempting this in Blender.

Now that I’ve created the map for winter solstice, I will begin work on a summer solstice version this week as well. Because unlike winter days that are dark and cold, summers in the north are too precious to spend days inside mapping!

You must be logged in to post a comment.